Honeycrisp Apples and Wealth Distribution

I’ve been doing a lot of reading recently about macroeconomics and wealth distribution. So obviously, in a moment of madness, I wrote a story about Honeycrisp apples.

Steve Jobs had a famously strange diet. He would go for weeks at a time eating only a single food, like apples.

As a thought experiment, imagine that the whole world is like Steve Jobs, and eats only apples. For simplicity’s sake, let's also assume these are all medium-sized Honeycrisp apples. The entire world has the exact same, undifferentiated preference. Let’s ignore for now the impossibility of growing enough apple trees, etc. etc.. Apart from the weird apple thing, the world is largely the same. This is a thought experiment after all.

What does the apple economy look like?

Does everyone grow their own apples in their backyards? Unlikely, but for a few 'live off the fat of the land' types. Are there regional growers that distribute to their respective geographies? Maybe. Does Amazon get into the apple growing and distribution business and produce apples more cheaply than anyone else, and become a monopoly? Much more likely.

Why does this happen?

For one, in our theoretical world, the entire food economy is commoditized. Whoever can most cheaply produce medium-sized Honeycrisp apples can afford to grow unabatedly (is that a pun?). There are no better apples or worse apples, so there is no need for differentiated producers. Competition is fought solely on the basis of productivity (i.e. who can produce and distribute the most apples at the cheapest cost?).

Also, this is the age of the internet. The internet creates leverage. Amazon can sell apples to everyone in the world. If Amazon can produce apples cheaper than anyone else, and sell them to everyone, they can squeeze out any competitors.

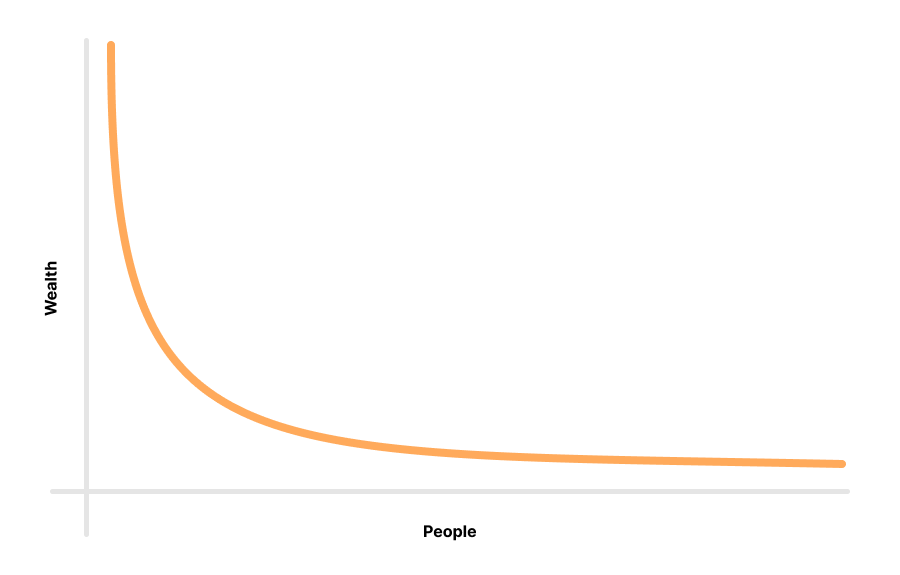

In this strange strange world the entire food industry has shrunk to a single entity. In 2021, the global food market produced $8 trillion in revenue. That is now all Amazon's. Needless to say, Jeff Bezos is now a trillionaire. His high-level managers and some other stockholders are billionaires. There are a hundreds of Amazon millionaires, and then there are millions of other Amazon employees who are doing ok. If you graph the net worth of all those employed in the food industry, who all work for Amazon, you’ll get an exponential curve, like the one below.

This type of curve is also known as a power-law distribution, or a Pareto distribution. These types of distributions are used to represent highly-skewed outcomes.

Ok, now what’s the point of this otherwise pointless story?

Point one, the Pareto outcome distribution is inevitable in free market economies (and all economies for that matter). For as long as there are records of wealth distribution in society, the wealthiest 1% dominate. All the way back in 1807, the top 1% of French people owned 44% of total wealth. Nearly everywhere scientists can observe outcomes, a Pareto distribution appears.

Point two, it is consumer demand for differentiated goods that tempers Pareto outcomes. In the real world, not everyone eats apples. There are people who like steak, tacos, and salads. Some people like to eat out, some people like to cook. Some people only drink shakes (is Soylent still a thing?). Each of these varied demands from consumers creates its own market for goods. The demand fractures the market into a million smaller chunks.

Now back to our fictional world. All of the sudden, the world snaps out of its strange apple obsession and assumes normal, varying food preferences. Amazon cannot possibly serve every single one of these consumer demands (though it may try), and so instead of a single entity dominating the food market, as Amazon had, thousands of firms spring into existence– each one serving a niche of consumer demand.

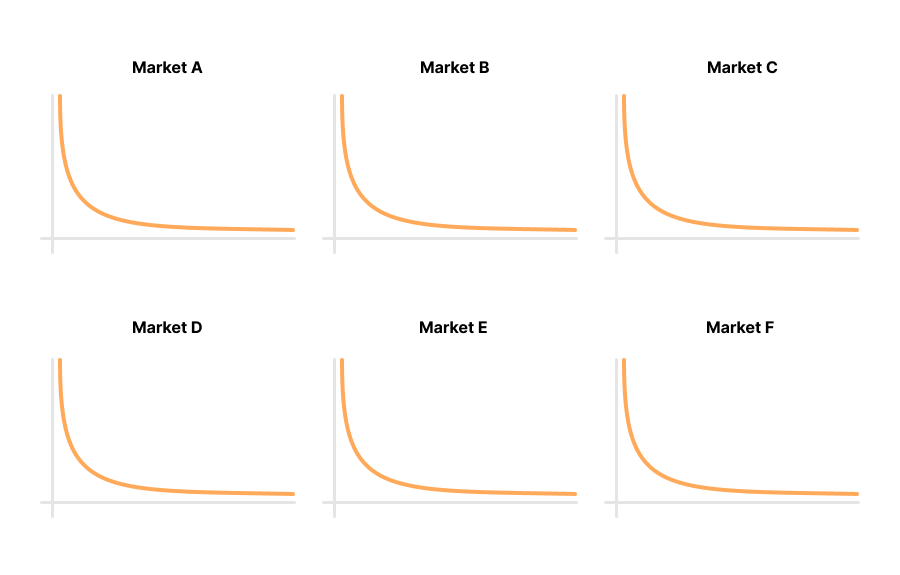

Instead of a single graph of wealth distribution for the food industry, there are now thousands, one for each demand niche. The sum total of wealth may be roughly the same, but it is now much more widely distributed, despite the fact that within each smaller chunk, the distribution pattern looks the same. Now there are thousands of smaller Pareto distributions.

All other things being equal, wealth is now distributed much more evenly within the food industry. The proliferation in the variety of consumer demand has tempered the Pareto distribution. Which seems like a reasonably good thing.

In order to achieve less skewed wealth outcomes, we want consumer tastes to vary widely. Luckily, this appears to be the natural progression of things. The author Matt Ridley says.

“The grand theme of human history is the increasing specialization of production combined with the increasing diversification of consumption.”

Specialization of demand breeds specialization of production, which breeds specialization of demand, ad infinitum. And specialization of demand is what fractures markets into smaller chunks. More companies, and more people get to win when there is a larger quantity of smaller markets.

It’s the economic equivalent to the big fish in a small pond idiom. Specialization of demand creates more big fish (producers) in more smaller ponds (markets).

Now, an obvious counter to this is: what about those companies that are able to serve the demand of many niche markets? Like our friends at Amazon? To them I say, you are right, some companies will be able to do that, and squeeze out smaller competitors, and ultimately accumulate wealth at a greater density.

But, is it not true that they will have a harder time serving more demand niches than fewer? In other words, it is less likely that a single entity will be able to dominate more markets than fewer markets.

And so, perhaps naively, I conclude that outcomes will never be distributed any way but by a Pareto distribution. So in order to maximize the distribution of wealth in a system, specialized demand is the key.

Create as many ponds as possible.