Pull Dynamics and the Virtual Marketplace

Push and Pull Dynamics

Chris Dixon wrote the first description of push and pull dynamics as a framework for understanding consumer behaviors on the internet in 2014. For those unfamiliar, pull dynamics are at play when an internet user is actively seeking information. A classic example of a pull dynamic is a Google search. Push dynamics are at play when a user is passively viewing information, such as when they are browsing a social media feed. Push and pull dynamics are a useful mental tool because most user actions on the internet fall neatly into one bucker or the other. Looking for a place on AirBnb? Pull. See a video on TikTok? Push. Browse a home on Zillow? Pull. See an ad on YouTube? Push.

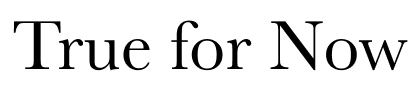

In the context of e-commerce, pull and push dynamics map to opposing ways of matching buyers and sellers, which in turn correspond to two acquisition models.

- Pull dynamics exist when buyers seek sellers. Marketplaces like Amazon rely on pull dynamics in the form of product searches.

- Push dynamics exist when sellers seek buyers. Independent direct sellers rely push dynamics in the form of social media and other paid advertisements.

Pull dynamics, where buyers seek sellers, are more valuable than push dynamics because they are associated with an intent to purchase by the buyer. Pull dynamics sometimes appear in disguise under the names ‘organic’ or ‘unpaid’ acquisition. Push dynamics, where sellers seek buyers, are weaker because the seller must persuade the buyer to make a purchase, and persuasion is a tricky business — it’s much better to find someone that doesn’t need persuading. Push dynamics are nearly synonymous with paid acquisition.

As an online seller, finding ways to benefit from pull dynamics is critical. We will see later how the direct sales model, which is typically associated with push dynamics, can start leveraging pull dynamics via something called the virtual marketplace.

But first, let’s look at the two sales models in more detail.

Marketplaces Pull, Direct Sellers Push

Amazon accounts for over 40% of all online retail in the US because of the power of pull dynamics (source). The 150 million Prime members literally pay Amazon for the privilege of shopping on their site (among other things). This takes the idea of buyers seeking sellers to the extreme — Prime members pay for access to its sellers.

How did Amazon achieve this dominant position?

One explanation is network effects. Network effects on Amazon work in the following way: buyers benefit from additional sellers, and sellers benefit from additional buyers, in a virtuous positive feedback loop. The way Amazon achieved this network effect is through it’s third party marketplace. Amazon’s third party marketplace enables independent sellers to compete for buyers on Amazon’s platform, and lets them benefit from Amazon’s user experience technology. The quantity of goods offered by third party sellers can scale much more quickly than can the goods offered first party (i.e. goods owned and inventoried by Amazon). This allows the positive feedback loop of network effects to spin even more quickly, creating a gravity-like pull, attracting both buyers and sellers.

A large percentage of direct sellers use the technology platform Shopify to host their stores. Combined, these Shopify-hosted stores sold $175.4 billion worth of goods worldwide in 2021, an increase of 47% over 2020 (source). In aggregate, Shopify hosted stores sold nearly 50% of the volume that third party sellers sold on Amazon’s marketplace, and the rate of sales growth is increasing twice as fast (source).

What makes that growth especially impressive is that, for the most part, stores hosted via Shopify rely on weaker push dynamics to attract their customers. Each individual Shopify store pays for social media and search ads to push buyers to their sites. A minority of revenue of direct internet sellers comes from organic, unpaid, traffic (source).

In recent years, due to technologies like Shopify dramatically reducing the barriers to entry for e-commerce entrepreneurs, the cost of a push-centric customer acquisition strategy (i.e. one relying on advertisement) has risen quickly, putting pressure on independent stores’ profitability. This is the essential weakness of the push model, it’s more expensive because it requires sellers to persuade buyers.

The illustration below shows the difference in push and pull dynamics between marketplaces and direct sellers today.

Push and Pull Dynamics Converge

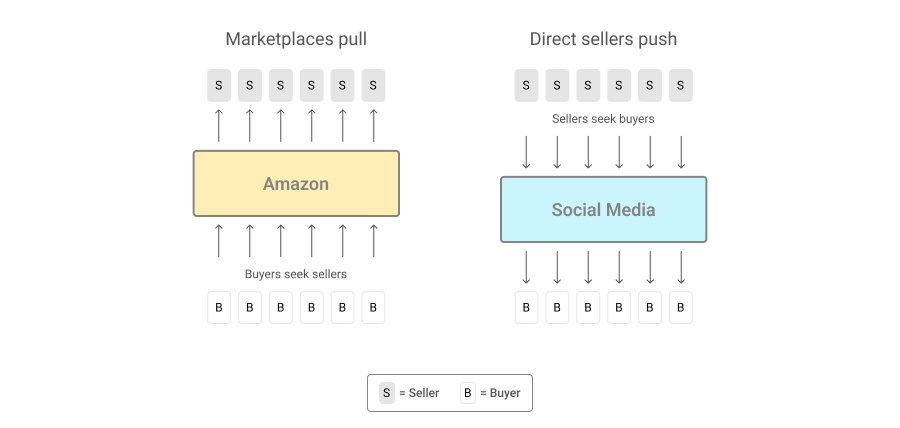

Today, the neat line separating push and pull dynamics is starting to erode on both ends. Amazon recently published their advertising revenue as a separate line item for the first time, it summed to $31 billion in 2021. That revenue is the sum of ad spend paid by sellers on Amazon looking to attract buyers via sponsored search rankings.

Amazon, which is still predominantly a pull-centric marketplace, has started to dilute the purity of its core functionality (to efficiently match sellers with buyers) by introducing the friction of paid results. This has the potential to degrade consumer trust in the platform, as the consumer senses that some of the utility of the platform is tainted. Whereas a search previously might’ve returned the best quality product based on customer reviews, that same search now returns a list of products sponsored by the deepest marketing budget. And as we’ve seen, ads are squarely in the push camp. Amazon is no longer purely a pull dominant, they are quickly moving toward a mixed dynamic.

Within the world of direct selling, paid social media ads and other push-centric methods have long been the dominant model of customer acquisition. Recent usage pattern changes on social media, especially by younger consumers, are starting to transform the utility of social media from push dominant, into a mix of push and pull. A 2020 report found that for younger women aged 16-24, social media platforms supplanted Google as the preferred platform for brand and product search, with males and millennials not far behind (source). Relatedly, TikTok stole the crown from Google as the most popular domain in the world in 2021, a title Google had held for over a decade (source). Consumers are starting to use social media platforms as search engines, creating pull dynamics that direct sellers can capitalize on.

TikTok, Reddit, Twitter are all much better search engines than Google

— Blake Robbins (@blakeir) March 8, 2022

The introduction of pull dynamics onto social media platforms is what transforms them into virtual marketplaces.

Virtual Marketplaces

First, let’s refresh what a marketplace is, and what properties make internet-native marketplaces so attractive to sellers (hint, it’s network effects). A marketplace is a platform that facilitates transactions between sellers of goods or services and buyers. When designed successfully, marketplaces benefit from network effects, as the presence of more buyers attracts more sellers, and the presence of more sellers attracts more buyers. Eventually, the sheer volume of sellers creates a force that pulls buyers into the marketplace.

Amazon’s marketplace operates exactly as described above, but now, social media platforms are starting to look like marketplaces too.

The question is, why weren’t social media platforms behaving as marketplaces before? They already had amassed tons of buyers, and nearly every seller already had a presence on the platforms. In some sense, a marketplace did exist, it just wasn’t functioning as such. It was inert because it was missing a key ingredient— pull dynamics. The buyers on social media were not behaving like the buyers on a marketplace, they weren’t there with the intention to shop, they were there passively, subject only to push dynamics. It was a mental block recently unstuck by two related changes:

- Consumer behavior changes driven by richer search results (i.e. more engaging content). As described above, younger consumers are seeking information (ding ding!) about products and brands on social media. Why are they doing this? Because product and brand research on Amazon is boring, quantitative, and review-centric, not to mention bogged down with ads. (And yes, I am aware that 50% of product searches start on Amazon, but this is an article about the future, not the present.) Young consumers want to hear a story, and social media is the place where the most stories are being told. Additionally, the volume of products available on Amazon and other marketplaces can be overwhelming, social media personalities can act as curators.

- Technology is blurring the lines between online stores and social media. Online storefront components like product pages, carts, and checkouts are starting to creep into the social media tech stack as composable elements. Linktrees and other link-in-profile services contain mini storefronts, shoppable posts allow users to checkout without leaving the platforms. Amazon’s monopoly on superior shopping user experiences is diminishing, for evidence of this, look no further than Shopify’s Shop Pay. And this is just the beginning, the lines between store and social will continue blurring.

Let’s now formally define what a virtual marketplace is. A virtual marketplace matches buyers and sellers, but it sits as a layer embedded within another experience, in this case, social media platforms. It is a marketplace that emerges from existing ingredients and consumer behaviors, without an explicit top down design. It is similar, but not identical to the currently en vogue social commerce, which is often defined as the combination of shopping and social media.

The key differentiator between a classic internet marketplace and a virtual marketplace, and a reason to be bullish on virtual marketplaces, is that the medium of information exchange becomes the style of media supported by the social media platform. Instead of a search returning boring product pages and endless reviews, as on Amazon, a search on a virtual marketplace returns richly produced stories and engaging videos. Real people and personalities act as curators of what is worth buying and what is not, rather than faceless reviews. And everyone knows stories are more convincing than statistics.

Now we can update our e-commerce models to reflect what is happening in terms of push and pull dynamics. As you can see, the models, at least from the perspective of push and pull dynamics, are now nearly identical.

While the two models will continue to converge (especially as Amazon introduces more social-like functionality, and TikTok starts selling search ads), it is likely that a new divergence will occur (or maybe already has occurred) to keep them separate. Certain product categories, those that benefit most from the subjective input of people and stories, will prosper in the virtual marketplace, and commoditized product categories will remain the bread and butter of classic marketplaces. (This idea is borrowed from this excellent write-up.)

Conclusion

Virtual marketplaces are still in their early days, slowly emerging from a primordial soup of technologies and behaviors. As the virtual marketplace gains recognition, direct sellers will require the help of content creators even more. Storytelling skill will become more important. Social media search optimization (SMSO? is that a thing?) will grow in importance. Dependence on paid advertising will fall. Social media platforms will probably seek to monetize by enforcing a take rate, or by starting their own paid search products.

Stay tuned for part two of this essay where I explore how Curation DAOs can participate as a critical spoke of the virtual marketplace, helping consumers identify trustworthy products, and helping brands tell their stories to the widest possible audiences.