The Optimistic Case for DAOs

The Goal of DAOs

“The question of whether decentralized or centralized systems will win the next era of the internet reduces to who will build the most compelling products...”. - Chris Dixon

Much has been written about the theoretical advantages of Decentralized Organizations (DOs), and Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) compared to typical organizational structures like corporations. Invariably, the advantages cited are: permissionless operations, transparency in resource allocation, elimination of managerial and bookkeeping inefficiencies, censorship resistance, and ease of fundraising. Many claim DAOs will be how the next generations of humanity will come together to solve problems, the ‘future of work’. But, are the above stated advantages alone enough to guarantee a future for DAOs?

The short answer is no, DAOs are not guaranteed an existence based on the supposed merits of their organizational structures alone. DAOs will have to compete against incumbent centralized models of organization, and can only survive by producing superior products and technologies.

** Author’s note: For the remainder of the essay, I will use the term DAO to refer to all Decentralized Organizations, DAOs, and DOs. I recognize that the term DAO is often used to describe organizations and projects that aren't strictly adherent to every principle of decentralization, or autonomy. I am knowingly perpetuating that here. **

Technology and Innovation

“Innovation emerges unbidden from the way that human beings freely interact if allowed.” - Matt Ridley

“When I came to Silicon Valley, I looked around and... I didn’t see a single genius inventor creating a single thing that suddenly changed the world. I saw, instead, lots of people doing lots of tinkering.” - Naval Ravikant

Technology is the useful application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, historically seen most often in industry (think machines in factories), but now seen across all industrial and consumer sectors. Technology is the result of unfettered pursuit of ideas by humans, directed toward the goal of improving the world; to make more stuff with less effort, to increase productivity. Humanity advanced from an agrarian society into modernity via the productivity advancements and wealth accumulation generated by technology.

Technology’s progression across time is called innovation. Innovation is an uncertain, emergent phenomenon, an evolution of trial and error. Better technology replaces worse technology in a never ending upward spiral, provided that the conditions of society are conducive to its progress (more on this below).

In some ways then, innovation is analogous to the scientific method, an empirical (i.e. observational) process that also progresses via trial and error. Using the scientific method, scientists develop hypotheses about the world, test their hypothesis via experimentation, observe the results of their experiment, and use the new observation to confirm the original hypothesis, or to form new hypotheses. This gets repeated until the best explanation emerges. The goal of the scientific method is to guide people toward developing better explanations about the world.

Innovation operates in much the same manner, but scientists are replaced by innovators, hypotheses are product ideas (i.e. inventions), and experimentation is conducted within the free market. A hypothesis is valid only if the market agrees, that is, if the product is able to produce a profit. The progress of innovation results not in a greater understanding of the world, but in a more productive and prosperous world.

There are at least three factors that influence (and certainly many more) the rate of innovation.

- The quantity of innovators/inventors. When more people pursue inventive activities, assuming the rate of successful invention remains constant, more technology will be produced, and innovation will result.

- The quality of hypotheses. Better hypotheses produce better products; those which are more likely to find buyers in the market. Put another way, an increase in the quality of hypotheses means that resources are allocated more productively. When poor quality hypotheses are formed, resources are allocated toward failed products, and innovation declines.

- The freedom for people to organize and pursue ideas. The introduction of regulatory friction can reduce the motivation of innovators, and limit innovation. Conversely, the relative lack of regulation within the internet domain has increased innovation.

It is important to note that these factors are not independent of one another. There is a complex dependency between them, most notably between the first (quantity of inventors) and the third (freedom). The goal of this article is to understand ways that DAOs can help improve any of the above three factors, and therefore, produce superior technologies, and quicker innovation.

The Beginning of Prosperity

The First Industrial Revolution began in mid-18th century Britain, and since its beginnings, the developed world has accumulated an unprecedented quantity of wealth and prosperity— the inevitable results of technological achievement and innovation. The First Industrial Revolution is a model for understanding how the conditions of a society can influence the rate of innovation. It is especially useful to investigate because, for the first time in history, the prosperity of the average person increased above it's historic, stagnant baseline (source).

Any attempt to describe what caused the First Industrial Revolution is destined to be futile, as it is a topic about which there is still much contention. But, there are several factors that are often cited in those debates, a non-exhaustive list of includes: scientific advancements inherited from the Scientific Revolution that preceded it, access to funding from accumulated mercantilism wealth, abundant natural resources and energy, relatively stable government and legal environment, and reasonably liberal economic policies (source).

In his book, The Most Powerful Idea in the World, William Rosen argues that the patent, an extension of property rights into the domain of ideas, played a starring role by incentivizing people to pursue invention at an unprecedented scale.

Curiously, the role the patent played was not primarily that it legally protected inventions from people seeking to copy them, as one might think. In fact, relatively few inventors of the period actually went through the trouble of formally patenting their inventions, and infringement was common (source). The patent was more important psychologically, as a motivation to invent. Another researcher of the Industrial Revolution puts it in clear terms, “...for the purpose of achieving technological progress, what mattered was not the actual working of the patents system, but the way it was perceived by inventors contemplating a project. There is considerable anecdotal evidence that the hope for a successful patent remained heavily on the minds of many of the great inventors of the age.” (source)

Before the patent was broadly understood, inventors did not perceive the potential financial and social upside that could be realized by their inventions. Pre-patent invention and experimentation was practiced by a smaller group of people: those wealthy enough to undertake it as a hobby, or those with financing from the state or other benefactors. The patent provided the necessary incentives, both financial and social, which broadened the number of people who wanted to create technology, increasing the quantity of inventors. After all, the desire to be rich and famous is not a modern invention.

This is not to say that the Industrial Revolution was solely caused by an uptick in the quantity of innovators. Other factors, notably the relatively free market, and stable government and legal structures, were also necessary conditions. But, the rising quantity of people seeking to profit in status and finance by creating new technology was a necessary, if not sufficient, part of the equation.

DAOs and Innovation

As seen in the case of the Industrial Revolution, innovation is clearly sensitive to external factors. What can DAOs learn from the Industrial Revolution to help spur the development of technology? How might the environment set by DAOs set the stage for another acceleration in innovation?

DAOs can increase innovation via two pathways.

- An increase in the quality of hypotheses, made possible by decentralized decision making.

- An increase in the freedom of people to pursue their ideas around the world, made possible by their internet-native constructions.

The Shortcomings of Centralized Decision Making

“Today, unaccountable groups of employees at large platforms decide how information gets ranked and filtered, which users get promoted and which get banned, and other important governance decisions. In cryptonetworks, these decisions are made by the community, using open and transparent mechanisms. As we know from the offline world, democratic systems aren’t perfect, but they are a lot better than the alternatives.” - Chris Dixon

It’s difficult to look at corporations and accuse them of somehow limiting the technological progress of humanity. If patents were the motivational fuel for inventors to pursue their ideas, corporations were the vehicles which allowed them to organize and scale their efforts to solve ever larger problems. Corporations also encouraged risk taking via the invention of limited liability, and enabled the pooling of capital resources via shared ownership. By peering deeper into the corporate structure, however, it is possible to spot weaknesses, especially in the related domains of information gathering and decision making.

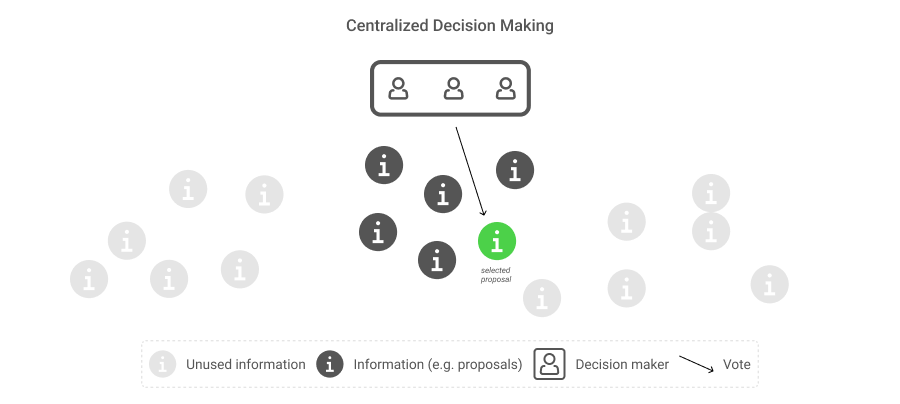

Corporations are naturally centralized, with a hierarchy that culminates at a small group of board members, or executives. Those leaders are accountable for the most important decisions, none more important than how to allocate the organization’s financial and human resources. In the framework of innovation, they decide which hypotheses are worth testing, and then fund the testing of those hypotheses with human and financial capital.

Oftentimes, the critique of centralized entities is that their hierarchical structures require centralized decision making, with the assumption that centralized decision making is inferior by its very nature. Decision making is the result of two things, gathering relevant information, and then applying logic to that information to decide on an action to take. Suboptimal decisions are made by a centralized organization as a result of the limitations in information gathering and errs in the logic used to determine the appropriate action.

For example, consider the government of the former Soviet Union, the archetypal centralized organization. In the Soviet economic system of central planning, a panel of government workers called the Gosplan was in charge of providing the state with recommendations on how to allocate the economy’s available resources (source). The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, partly due to the failure of this panel to properly recommend resource allocation decisions.

The reason that the Soviet centrally planned economy failed was not that the decision making was centralized, per se, but that the Gosplan was unable to gather and synthesize enough information from the real world to make the correct allocation decisions. This is the problem described by the economist Freidreick Hayek as the local knowledge problem. Formally, it is defined as a problem where the required information to make allocation decisions is not available to any single entity, it is distributed among the individual actors within the economy.

The quantity of information that can be processed by the combined intelligence of millions of participants in a decentralized, free market economy, far outweighs the quantity of information that can be processed by a centralized organization. As a result, the allocation of resources, the decision making, that emerges from a decentralized group of actors is done with more intelligence than is possible from any centralized equivalent. This concept is known as collective intelligence.

Again, invoking the criteria for innovation from above, centralized entities are forced to limit the amount of information that they can evaluate within their decision making process. This sets the conditions for a suboptimal decision making in the allocation of resources. Centralized decision making produces lower quality hypotheses.

This is not to suggest that operating a business is the same as operating an entire economy, they are obviously different activities. The argument is agnostic to scale. Greater information processing capability can produce better decision making, and that is only achievable within a decentralized decision making process.

Decentralized Decision Making in DAOs

For organizations, the value of information is to improve decision making. - Boon Kim Tan

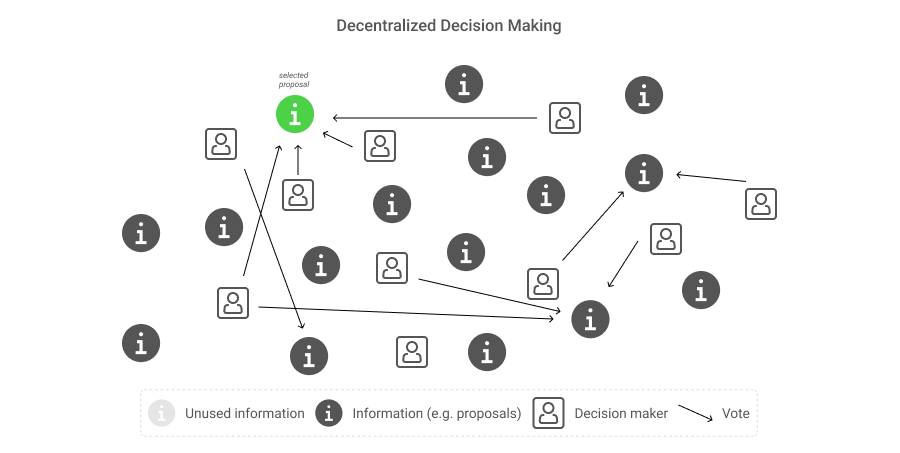

DAOs must make the same types of decisions that centralized corporations make, among which resource allocation, or, deciding which hypotheses to pursue, is the most important. The difference between the two organizational structures is in how they make those decisions. Functionally, a DAO makes decisions by receiving, evaluating, and voting on proposals. A proposal is a unit of information that describes any possible action that the DAO might undertake. Any DAO member can submit a proposal. To decide which proposals to execute, a DAO hosts a voting mechanism, in which every DAO member is able to submit their opinion on whether the proposal is worth executing or not. In a DAO, all resource allocation decisions are the result of a proposal that successfully meets a threshold of support among the voting members. The process just described is decentralized decision making.

Decentralized decision making is possible in DAOs because the formal management hierarchy is dissolved in favor of programmatic management. The management layer of a typical organization is replaced with software. When management becomes software, management adopts the advantages of software, like its ability to scale easily. Scalable management enables the quantity of participants in the decision making of the organization to scale indefinitely, which unlocks a potential for information processing that is not feasible otherwise.

Similar to how the decisions made by a centralized organization are not by definition inferior, the decisions made by a decentralized organization are not always superior. Decentralized decision making has a higher upper bound of potential quality, but reaching that bound is not a given.

The upper bound can only be realized when the individuals (or other entities) that participate in the decision making process submit a diversity of plausible proposals, and when consensus on what proposals to pursue is coordinated effectively. This argument for a DAO’s superior decision making assumes the former (that individuals contribute diverse proposals), and takes for granted that solutions that enable the latter (successful coordination) will be created.

As we saw in the discussion of free market vs. centrally planned economies, the ability to effectively coordinate the knowledge from a large number of people, or other information bearing entities, is the superpower of decentralized decision making. A DAO extends this concept into the realm of organizations, and creates the conditions that enable an increase in the quality of the hypotheses in the form of product ideas, and resource allocation decisions.

Restricted Freedom and Innovation

“Innovation is the child of freedom and the parent of prosperity.” - Matt Ridley

I am writing this article from within the borders of a democratic western country, the US, and so it’s relatively difficult for me to imagine an environment where freedom is not the default state of affairs. Yet, according to a 2022 report from Freedom House, only 20% of the world’s population live in free societies, and nearly 40% live in restrictive, often authoritarian societies (source). One reason a restrictive geography hurts innovation is because the vehicle that inventors need in order to organize talent, and attract funding— a centralized corporate entity — is governed by the whims of the local regulatory environment.

Consider the options of a person in a restrictive geography. In order to assemble themselves to build technologies, they must either physically exit their geographies (if they can at all) for a geography that is more free, or somehow reform the political and economic policies within the geography that they live. The former alternative may be illegal and/or impossible, and the latter nearly incalculably difficult. They are trapped by their physical circumstances, and innovation is stopped because they do not have the freedom to organize and pursue their ideas.

DAOs, Freedom, and the Internet Jurisdiction

The internet is an inherently free jurisdiction because its underlying protocols are open for anyone to build on. The internet operates (mostly) outside the influence of any government or other entity that might seek to control it. This freedom from regulation is part of the reason why there has been such enormous growth in internet-based technologies in recent decades. Innovators are able to easily test things out, fail, and try again. The emergent, trial and error process of innovation is able to operate unconstrained on the internet because of its freedom. DAOs are internet-native organizations, meaning they exist, like the internet itself, outside the control of any nationstate. DAOs are also permissionless, meaning anyone with internet access can join them, from anywhere.

The nearly 40% of people who are living in part of the world with limited freedom require only a connection to the internet to start or participate in a DAO. This is a step change improvement over the current state of the world, where billions of people lack the ability to come together and solve problems with their intellect, because of where they live.

The internet enabled any person with access to the internet to publish code and try to create value with the utility of that code. A DAO takes that ability and generalizes it to the scale of an organization. Now any person with access to the internet can publish a mission statement in code, and create value by fulfilling the promise of that mission, with the help of any other internet user who wants to contribute.

This increases the rate of innovation by increasing the freedom for people to pursue their ideas.

Conclusion

DAOs must compete, and win, against their centralized equivalents in the race to produce superior technology products if they are to achieve a stable position in professional society. Technological progress is sensitive to both macro-scale factors, like the freedom and stability of a society, and to micro-scale factors, like the quality of decision making at the individual organizational level. DAOs are unique in their ability to affect both types of factors. On the macro-scale, they are vehicles for organization that are untethered from the restrictions of governments. On the micro-scale, they are capable of producing superior decisions by harnessing the power of collective intelligence.

Discussion

The topic explored above is clearly very much speculation and as such, contains countless points that will invite argument, especially, I suspect, around the viability that the "programmatic management" problem will be solved, and DAOs’ ability to generally produce real-world technologies. Pushback against these ideas is welcomed. Additionally, I am not a historian, and so have painted the Industrial Revolution and Soviet economic policy in very broad strokes. Any mischaracterizations caused by this approach are my own.