DTC, meet DAO

Bootstrapping customer acquisition in a new era of online commerce.

Bonobos co-founder Andy Dunn writes the following about the idea that helped propel his brand to success in its early years. “Ten years ago, our unique insight was that the future of vertical retail would be digital at its core. We architected our entire strategy around that founding idea.” Read in 2022, “digital at its core” does not sound like a uniquely insightful concept, but in 2007, when Bonobos was founded, it was a unique insight. The first iPhone was released that year. In 2007, only 3% of retail sales occurred online— today it’s more than 4 times higher (source). Less than a year prior to Bonobos’s launch, Pew Research had found that just 11% of US adults used social media, today more than 70% of adults do (source).

To build a digital first consumer brand in that world was not obvious, and that is precisely why it had a chance to succeed.

A Harvard Business Review describes why the first digital first “direct to consumer” brands like Bonobos succeeded. “The direct-to-consumer startups’ rise was enabled by an environment of abundant venture capital, low competition, and above all, the advertising arbitrage that could be exploited on under-priced social media platforms.” (emphasis mine)

The first digital consumer brands succeeded because they were non-consensus (i.e. had low competition), well-funded, and because they benefited from technological and social tailwinds (i.e. the millions of potential consumers gathering on social media for the first time). To be clear, attributing all of their success to these things is to greatly discount their achievements. The most successful brands of the era also created awesome products, a requirement regardless of the time period. But, it’s undeniable that one key factor to their success was their recognition and leveraging of the underlying technology shifts that were happening at the time.

It’s 2022, and another new technology stack has emerged, web3, which, in turn, has generated another new set of human behaviors. What types of opportunities might be capitalized on by the next wave of digitally native consumer brands? In addition, why is it worth exploring web3 for e-commerce? Is it really useful to mash these two concepts together just because?

Web2 vs web3

The remainder of this article will be much more clearly understood if we define some terms first, namely: web2, and web3.

The Ethereum foundation defines web2 as follows: “the version of the internet most of us know today. An internet dominated by companies that provide services in exchange for your personal data.” Google, Meta, Twitter, and the like are the companies that are most widely associated with web2.

Web3, on the other hand, refers to a basket of technologies and applications that are built on top of a censorship resistant blockchain(s). The fundamental goal of web3 is to build a new internet that is not reliant on 3rd party platforms like Google, Meta, et al. Sometimes web3 is referred to as an internet ‘owned’ by the people.

web1: read

— cdixon.eth (@cdixon) February 8, 2022

web2: read, write

web3: read, write, own https://t.co/VtJMsQzTE8

Why explore web3 and dtc e-commerce

Recall the factors that enabled brands like Bonobos to succeed. They were: low competition, access to funding, and relatively cheap digital advertising. Today, things in the direct-to-consumer e-commerce space look much different, especially concerning competition and the price of digital advertising.

Competition

Competition among e-commerce companies is now high. Technologies like Alibaba (product sourcing), Shopify (storefront hosting), and 3PLs (3rd party logistics for warehousing and shipping) eliminate most of the barriers to start an e-commerce business. Tech founder and investor Naval Ravikant puts it succinctly. “It's never been easier to start a company. It's never been harder to build one.” Although his statement is referring to tech businesses, it applies just as well to online commerce businesses.

Increased competition is generally a good thing for consumers; they benefit from more choices and lower prices, but a bad thing for businesses. Starting an e-commerce business inside the web2 paradigm is now almost trivial, but building a viable business, one that makes money, has never been more difficult.

Digital advertising

Digital advertising was one tool that enabled digitally native brands to scale their customer acquisition widely in the early days of paid search, and paid social media. Today, paid search and paid social media advertising make up 50% of total US online marketing spend (source). A considerable percentage of new customer acquisition for e-commerce businesses is facilitated through these ads placed on Instagram/Facebook and Google, who combined take 90% of new online ad spending (source).

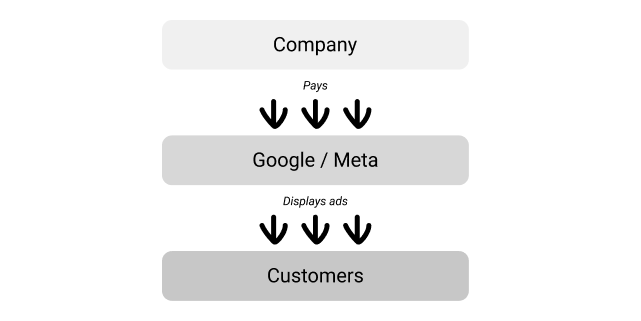

The behemoths that grew out of the web2 world, Google and Meta, are the new landlords of commerce. An Economist article from 2020 describes the tradeoff online sellers make by not paying to be in physical stores, “Online retailers save on physical shopfronts but must maintain a visible virtual presence...”. To make the analogy even more explicit, online retailers must pay “rent” in the form of digital ad spend to their “landlords”, Google and Meta (and Amazon, but marketplace commerce is not covered in this article), in order to be considered by shoppers. The below diagram shows what this looks like.

As competition for shoppers attention has risen, and the privacy changes made by Apple have degraded ad relevance, the “rent” paid by e-commerce merchants has risen in lockstep. For online merchants, this results in higher customer acquisition costs, and less attractive unit economics, or in other words, an unprofitable business model.

To summarize, web2 has done a tremendously good job at building the tooling to help entrepreneurs start and scale e-commerce businesses, maybe too good of a job. This has created a hyper competitive market, which has resulted in rising customer acquisition costs, and a bottleneck to reach customers on giant, demand-aggregating platforms.

Web3 and e-commerce

In the same way that the invention of social networks and online search seeded new opportunity for a generation of online commerce founders, web3 introduces a new set of technologies that provide an opportunity for similarly-minded founders to re-invent digital commerce, again.

Founders will encounter a number of new digital primitives including: NFTs, DAOs, Tokens, Wallets, Defi. Each of these primitives can underpin new approaches to things like customer acquisition, business formation and organization, brand creation, customer loyalty, payment processing, etc..

The most transformational of all these technologies might be DAOs...let’s first look at what they are, and then how they can support alternative models of customer acquisition. (N.B. There are tons of even more interesting things that DAOs might enable, and they will be covered in later posts.)

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs)

A comprehensive discussion of DAOs is outside the scope of this article (and the author’s expertise), so for the purposes of this article, it’s important only to understand the following properties of a DAO:

- A DAO is organized around a mission– what is the purpose of it existing?.

- Anyone can be a member of a DAO, provided they control some amount of the DAO’s token (sometimes the tokens are NFTs).

- The DAO’s token/NFT grants its holders rights to submit and vote on proposals. The rights are coded into the governance of the DAO, and can be changed.

- Member incentives are aligned via the DAO’s token/NFT, which should accrue value if the DAO succeeds. In other words, every member is an owner of the DAO and theoretically benefits financial from its success.

- A DAO automatically executes approved proposals. Typically this means that funds are directed somewhere, or for tech products, code is altered.

In a single sentence, a DAO is a group of people, with shared goals and financial interests, working to solve a problem, facilitated by a governance mechanism. DAOs are also generalizable, they don’t have to build crypto-related products, they can be formed to solve any type of problem.

Incentive alignment

DAOs can raise capital much more easily than other organizational structures because the process of funding a DAO is incredibly simple— all you need to do it send funds to a crypto wallet. A great example can be found in the ConstitutionDAO, who’s mission was to buy a copy of the US Constitution, raised over $40mm in days, from thousands of random people. ConstitutionDAO instantly had thousands of stakeholders, all of whom previously were strangers to one another, but were suddenly aligned around a single mission.

Let’s briefly jump back to the early days of Bonobos, to examine a similar story about stakeholder alignment. Andy Dunn writes about an early funding round of Bonobos, “over forty investors and early customers contribut[ed]. It was a “long cap table”, but we thought it was worth it to have our early adopters spreading the word with skin in the game.” He goes on to describe that one of the early investors even started selling pants out of his apartment. Dunn wanted to complicate the capital raise in order to incentivize as many people as possible to contribute to the success of the brand. In his mind, the more stakeholders whose financial incentives were aligned with the business, the better.

Why is it important to maximize the number of people aligned around the mission? Why did Dunn want that for Bonobos? In his own words, he wanted to maximize the number of people ‘spreading the word’. Spreading the word is a euphemism for the most vital activity of any business, sales. But does giving a large number of people ‘skin in the game’ really work?

NFTs and ‘shilling’

Conveniently, there is already an example of this behavior in action, in another corner of the web3 space, NFTs. Specifically, the NFT projects that create and sell digital artwork, and sometimes do other things too, like grant access to private online and/or real life communities. The NFT holders of these projects are incentivized to promote (”shill” in slang terms) the NFTs that they hold because the value of their NFT will increase in proportion to demand, as the supply of the NFTs is fixed. The better the community of holders is at shilling the project, or, the more demand the community can create for the NFTs, the more valuable their collective holdings become. It is a deceivingly simple incentive structure, but it works.

At a first order of approximation, incentives for DAO members are the same as they are for NFT holders. The more demand each DAO member can generate for whatever product the DAO sells, the more valuable their share in the DAO will become (either through a cut in the DAOs profits, or some other value accrual mechanism).

But there exist crucial differences between the two ideas, primarily driven by the differing nature of the underlying ‘products’. NFT holders are selling membership to an exclusive club, who’s membership is represented by the NFT. A DAO member’s primary objective isn’t to sell membership in the DAO, it’s to sell the physical products produced by the DAO. The two models therefore have significantly unique value propositions, NFT holders seek to communicate successfully that their club is cool and worth joining, while DAO members need to communicate something more specific, namely, whatever value their product provides.

The methods DAO members can use to sell their products are where things get really interesting.

Influencer + DAO member

To recap, a DAO enables a large number of people to align around a common mission, and provides those people with powerful financial incentives to achieve that mission.

One potential sales channel involves blurring the lines between DAO members and influencers.

Consumers want to be Influencers

— cantino.eth (@chriscantino) February 21, 2022

Influencers want to be Founders

Founders want to be Investors

Investors want to be Consumers

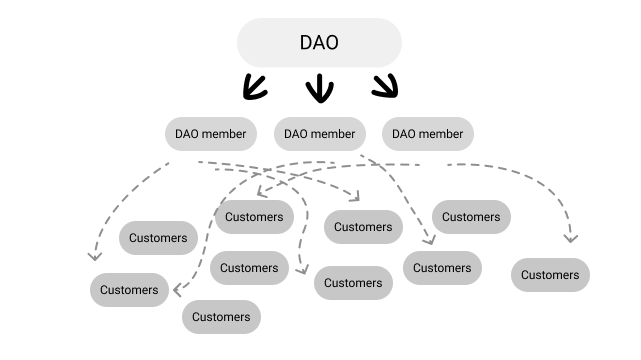

Imagine a DAO that distributes, or sells, membership NFTs to a network of 1,000 “influencers”. The DAO could choose to airdrop the NFTs for free, in which case the “cost” is measured by the dilution of the remaining DAO members. If they choose instead to sell the membership NFTs, then the DAO is cashflow positive for that transaction.

The NFTs represent membership in the DAO, members can vote on and submit proposals (as previously discussed), and in this case, members might also have a right to dividend distributions on the profits generated by the DAO. This arrangement runs into sticky legal questions regarding whether that NFT is a security, alternatively, each membership NFT might provide its holder with an affiliate link that automatically earns the holder a percentage commission on each sale they generate.

The financial wellbeing of the member influencer is now aligned with the long-term success of the DAO, and one obvious way to increase the success of the DAO is to promote the product and generate sales — a skill these member influencers already have.

One crucial difference in this model, especially when compared to the web2 “landlord/rent model”, is that the DAO is not subject to the same upward pressures on customer acquisition, dictated by the web2 platforms on which they are reliant since the price is determined by the DAO itself (i.e. how much the DAO is willing to pay each influencer for a sale).

In addition, the member influencers are incentivized to help the brand over the long term, since their expected financial rewards scale with success of the DAO, via the appreciation in the value of their membership NFT. This incentive model is also well-known among startup founders, who often cannot afford to pay high-salaries, and so attract highly talented people with equity. In our example, the sales model looks something like the following:

One legitimate critique of this model regards the question of scale. In a web2 world, because the vast majority of possible customers are aggregated on Google and Meta, marketing can scale almost infinitely, provided the company has the cash to pay for it. Is it possible to scale the influencer member model?

Composability of DAO tokens

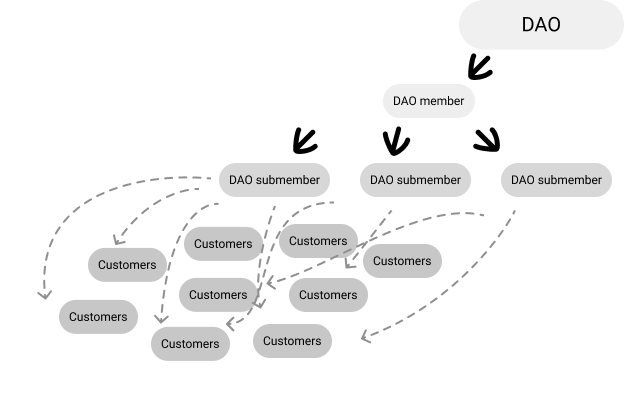

Let’s take this possibility one step further, and introduce the concept of composability, a feature unique to web3 technologies. Composability means that web3 digital primitives like tokens and NFTs can be built on top of in a permissionless way. Anyone can write code and expand the features of an existing digital asset.

Let’s say some of the individual influencer members want to scale their efforts to increase the reach of the marketing effort. Because the NFT they hold is composable, they could conceivably break it up into “smaller” NFTs, each of which gets pro rata (or discounted) privileges, and then sell those to other people who might want to get involved. There is essentially no limit to the amount of times this could be done. This model might look something like the following:

Open Challenges

Of course, until this model is tried in the real world, it remains theoretical. There exist challenges, not limited to the legality of selling equity-like NFTs, and the unproven nature of a fully influencer/member salesforce.

The specific channels and methods that these member/influencers might use to generate sales is deliberately overlooked here. Suffice to say, it’s likely that every and all existing online communication tools will be tested.

It’s also quite likely that this sales model will inevitably reach an asymptote, past which it cannot scale. There are no brands that rely on only a single model of customer acquisition. This is the reality of all commerce, acquisition is always mixed across channels.

Closing thoughts

I can't believe this needs to be said but being decentralized and/or having a token is not a replacement for building things people want

— sariazout.eth (@sariazout) February 16, 2022

One thing that a DAO absolutely will not be able to do is turn a crappy product into a successful business. Selling a lousy product online via any DAO model will fail, just like selling a lousy product via any other organizational model will fail.

The long term vision is that DAOs help to coordinate and incentivize people and their ideas in a manner superior to traditional, top-down corporate structures. In so doing, a DAO sets the conditions for the creation and delivery of superior products — products that are better than those created by their centralized counterparts.

Here's to that vision becoming a reality.